They Never Rule Over Him

“‘This Brahmin,’ he said to a friend, ‘is no proper merchant and will never be one, there is never any passion in his soul when he conducts our business. But he has that mysterious quality of those people to whom success comes all by itself, whether this may be a good star of his birth, magic, or something he has learned among Samanas. He always seems to be merely playing at the business affairs, they never fully become a part of him – they never rule over him, he is never afraid of failure, he is never upset by a loss.’

The friend advised the merchant: ‘Give him from the business he conducts for you a third of the profits, but let him also be liable for the same amount of the losses, when there is a loss. Then, he’ll become more zealous.’

Kamaswami followed the advice. But Siddhartha cared little about this. When he made a profit, he accepted it with equanimity; when he made losses, he laughed and said: ‘Well, look at this, so this one turned out badly!’”

– Hermann Hesse, Siddhartha

Thomas Merton | Being Ourselves

The following audio is from Thomas Merton’s On Contemplation.

The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness

“C.S. Lewis in Mere Christianity makes a brilliant observation about gospel-humility at the very end of his chapter on pride. If we were to meet a truly humble person, Lewis says, we would never come away from meeting them thinking they were humble. They would not be always telling us they were a nobody (because a person who keeps saying they are a nobody is actually a self-obsessed person). The thing we would remember from meeting a truly gospel-humble person is how much they seemed to be totally interested in us. Because the essence of gospel-humility is not thinking more of myself or thinking less of myself, it is thinking of myself less.

Gospel-humility is not needing to think about myself. Not needing to connect things with myself. It is an end to thoughts such as, ‘I’m in this room with these people, does that make me look good? Do I want to be here?’ True gospel-humility means I stop connecting every experience, every conversation, with myself. In fact, I stop thinking about myself. The freedom of self-forgetfulness. The blessed rest that only self-forgetfulness brings.

True gospel-humility means an ego that is not puffed up but filled up. This is totally unique. Are we talking about high self-esteem? No. So is it low self-esteem? Certainly not. It is not about self-esteem. Paul simply refuses to play that game. He says ‘I don’t care about your opinion but, I don’t care that much about my opinion’ – and that is the secret. A truly gospel-humble person is not a self-hating person or a self-loving person, but a gospel-humble person. The truly gospel-humble person is a self-forgetful person whose ego is just like his or her toes. It just works. It does not draw attention to itself. The toes just work; the ego just works. Neither draws attention to itself.

Here is one little test. The self-forgetful person would never be hurt particularly badly by criticism. It would not devastate them, it would not keep them up late, it would not bother them. Why? Because a person who is devastated by criticism is putting too much value on what other people think, on other people’s opinions. The world tells the person who is thin-skinned and devastated by criticism to deal with it by saying, ‘Who cares what they think? I know what I think. Who cares what the rabble thinks? It doesn’t bother me.’ People are either devastated by criticism – or they are not devastated by criticism because they do not listen to it. They will not listen to it or learn from it because they do not care about it. They know who they are and what they think. In other words, our only solution to low self-esteem is pride. But that is no solution. Both low self-esteem and pride are horrible nuisances to our own future and to everyone around us.”

– Timothy Keller, The Freedom of Self Forgetfulness

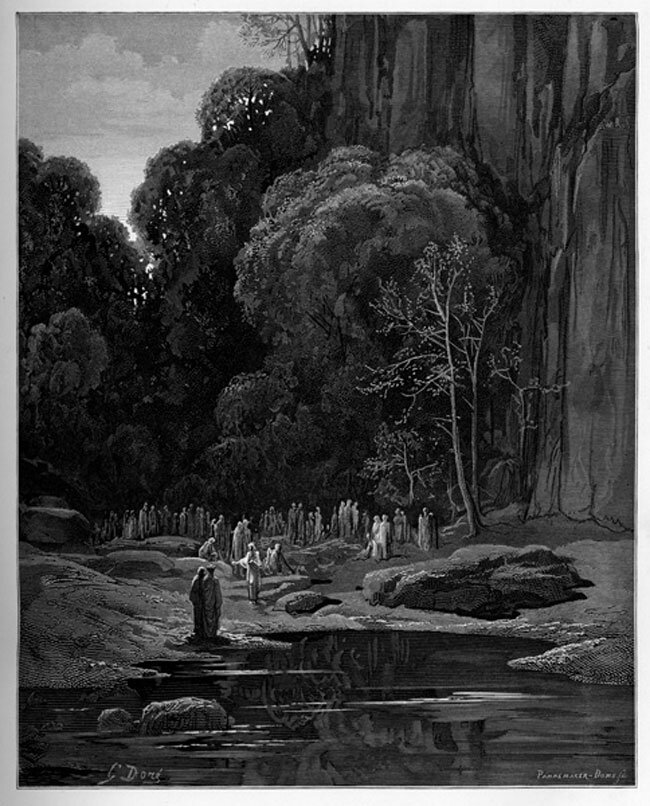

The Mount of Purgatory

The image below is a painting by Gustave Dore, depicting Dante and Virgil at the base of the Mount of Purgatory. I am currently reading The Divine Comedy. Richard Beck recently did a wonderful series on Dante and the Divine Comedy starting here.

Life as purgatory – as a process of purification – is an image that appeals to me. Life as soul development.

Alone in a Dark Wood

The Man Who Was Thursday, Job, and The Problem of Evil

One day the angels came to present themselves before the Lord, and Satan also came with them. The Lord said to Satan, “Where have you come from?”

Satan answered the Lord, “From roaming throughout the earth, going back and forth on it.”

Then the Lord said to Satan, “Have you considered my servant Job? There is no one on earth like him; he is blameless and upright, a man who fears God and shuns evil.”

“Does Job fear God for nothing?” Satan replied. “Have you not put a hedge around him and his household and everything he has? You have blessed the work of his hands, so that his flocks and herds are spread throughout the land. But now stretch out your hand and strike everything he has, and he will surely curse you to your face.”

– Job 1:6-11

"I see everything," he cried, "everything that there is. Why does each thing on the earth war against each other thing? Why does each small thing in the world have to fight against the world itself? Why does a fly have to fight the whole universe? Why does a dandelion have to fight the whole universe? For the same reason that I had to be alone in the dreadful Council of the Days. So that each thing that obeys law may have the glory and isolation of the anarchist. So that each man fighting for order may be as brave and good a man as the dynamiter. So that the real lie of Satan may be flung back in the face of this blasphemer, so that by tears and torture we may earn the right to say to this man, 'You lie!' No agonies can be too great to buy the right to say to this accuser, 'We also have suffered.' It is not true that we have never been broken. We have been broken upon the wheel. It is not true that we have never descended from these thrones. We have descended into hell. We were complaining of unforgettable miseries even at the very moment when this man entered insolently to accuse us of happiness. I repel the slander; we have not been happy. I can answer for every one of the great guards of Law whom he has accused.”

– G.K. Chesterton, The Man Who Was Thursday

Jesus as Apocalyptic Prophet in the Gospel of Matthew

As a follow-up to the Historical Jesus Series, I just released Jesus as Apocalyptic Prophet in the Gospel of Matthew. I realize this is a controversial subject matter, but it is one that has profound implications for the life of faith. In my opinion, this topic has been almost completely ignored by the modern church. Whether one agrees with the conclusions presented in this essay or not, “Jesus as Apocalyptic Prophet” is a view that any serious student of the New Testament will at least need to engage. Personally, although this subject matter was distressing to me when I first encountered it, I believe it ultimately led to a broader and more life-giving understanding of religion and spirituality. More information about this tract can be found on the My Books page.

Luminous Dusk | Soldiers

“My late father fought in the Second World War as an enlisted man. He told me that he discovered what he was up to only after he returned home and read a few books. In the midst of battle, ignorance and confusion governed. Knowledge consisted of concrete imperatives: go left, retreat, hold your fire, cross the bridge, walk the road, take the town. How his deeds furthered some master plan he knew not: there was for him no big picture. My father could not see the forest because he was a tree. He just followed orders and tried to stay alive. Those of us who are religious are like my father. We know that we are in a war but not how it goes or how it will eventuate; and few of us are generals. Our lot is rather to be good soldiers – to live according to the imperatives upon us and to save our souls.”

– Dale Allison, The Luminous Dusk

This quote very much reminds me of Viktor Frankl’s thought. We don’t know the ultimate meaning of life. In the absence of that knowledge we have to ask ourself what our meaning is. What is life calling us to?

Effects and Interpretation

I am more certain than ever that the practice of Centering Prayer, over the long run, leads to positive changes in my life. I am less certain than ever how to interpret what is actually happening during Centering Prayer.

Life As It Is

I’m kind of on a spiritual high right now. When I’m on a high, my problems aren’t gone, but I feel like I’m 100% ok that they are there. I’m 100% ok with life as it is. My problems are there, but they don’t matter.

Phrases like “non-craving” and “non-striving” come to mind.

Thomas Merton | Passive Prayer

To end this series, I’d like to post some brief audio from a collection called Thomas Merton on Contemplation. In this collection, Merton speaks about a wide variety of topics surrounding prayer and the contemplative life. Here, he addresses “passive prayer” – which is often how Centering Prayer, my own personal practice, is described.

A related quotation about passivity that I can’t pass up listing with this post comes from Aldous Huxley’s The Divine Within: Selected Writings in Enlightenment.

"Now, very briefly, I must just touch on the means for reaching this state. Here, again, it has been constantly stressed that the means do not consist in mental activity and discursive reasoning. They consist in what Roger Fry, speaking about art, used to call ‘alert passivity,’ or ‘determined sensitiveness.’ This is a very remarkable phrase. You don't do anything, but you are determined to be sensitive to letting something be done within you. And one has this expressed by some of the great masters of the spiritual life in the West. St. Francois de Sales, for example, writing to his pupil, St. Jeanne de Chantal, says: 'You tell me you do nothing in prayer. But what do you want to do in prayer except what you are doing, which is, presenting and representing your nothingness and misery to God? When beggars expose their ulcers and their necessities to our sight, that is the best appeal they can make. But from what you tell me, you sometimes do nothing of this, but lie there like a shadow or statue. They put statues in palaces simply to please the prince's eyes. Be content to be that in the presence of God: he will bring the statue to life when he pleases.'"

Thomas Merton | Starting From Being

The final quotation for the Merton series comes from his Zen and the Birds of Appetite. A longer term project I have is to write a tract/book on comparative apophatic spiritual practice. This quotation seems to fit perfectly for that project.

“...let us remind ourselves that another, metaphysical, consciousness is still available to modern man. It starts not from the thinking and self-aware subject but from Being, ontologically seen to be beyond and prior to the subject-object division. Underlying the subjective experience of the individual self there is an immediate experience of Being. This is totally different from an experience of self-consciousness. It is completely nonobjective. It has in it none of the split and alienation that occurs when the subject becomes aware of itself as a quasi-object. The consciousness of Being (whether considered positively or negatively and apophatically as in Buddhism) is an immediate experience that goes beyond reflexive awareness. It is not ‘consciousness of’ but pure consciousness, in which the subject as such disappears.

Posterior to this immediate experience of a ground which transcends experience, emerges the subject with its self-awareness. But, as the Oriental religions and Christian mysticism have stressed, this self-aware subject is not final or absolute; it is a provisional self-construction which exists, for practical purposes, only in a sphere of relativity. Its existence has meaning in so far as it does not become fixated or centered upon itself as ultimate, learns to function not as its own center but ‘from God’ and ‘for others.’ The Christian term ‘from God’ implies what the nontheistic religious philosophies conceive as a hypothetical Single Center of all beings, what T.S. Elliot called ‘the still point of the turning world,’ but which Buddhism for example visualizes not as ‘point’ but as ‘Void.’ (And of course the Void is not visualized at all.)

In brief, this form of consciousness assumes a totally different kind of self-awareness from that of the Cartesian thinking-self which is its own justification and its own center. Here the individual is aware of himself as a self-to-be-dissolved, in self-giving, in love, in ‘letting-go,’ in ecstasy, in God – there are many ways of phrasing it.

The self is not its own center and does not orbit around itself; it is centered on God, the one center of all, which is ‘everywhere and nowhere,’ in whose all are encountered, from whom all proceed. Thus from the very start this consciousness is disposed to encounter ‘the other’ with whom it is already united anyway ‘in God.’”

Thomas Merton | Disposition to Humility and Pliability

“The gift of prayer is inseparable from another grace: that of humility, which makes us realize that the very depths of our being and life are meaningful and real only in so far as they are oriented toward God as their source and their end.

...even the capacity to recognize our condition before God is itself a grace. We cannot always attain it at will. To learn meditation does not, therefore, mean learning an artificial technique for infallibly producing ‘compunction’ and a ‘sense of our nothingness’ whenever we please. On the contrary, this would be the result of violence and would be inauthentic. Meditation implies the capacity to receive this grace whenever God wishes to grant it to us, and therefore a permanent disposition to humility, attention to reality, receptivity, pliability.”

Thomas Merton | Brothers and Sisters

Recently, I’ve been consciously trying to see people in the world as my “brothers and sisters.” There is something about that mental category that seems to put me in the right frame of mind to appropriately see, and treat, everyone I encounter.

A Thomas Merton passage comes to mind, from Zen and the Birds of Appetite:

“The self is not its own center and does not orbit around itself; it is centered on God, the one center of all, which is ‘everywhere and nowhere.’ in whom all are encountered, from whom all proceed. Thus from the very start this consciousness is disposed to encounter ‘the other’ with whom it is already united anyway ‘in God.’”

If it is true that we all united by the same Source, then we truly are brothers and sisters.

A similar idea, from a more traditionally Buddhist point of view, came out when I was writing A Great Tragedy:

“Things were good for this group of six and life had been kind to them until this point. Tony was, in fact, sometimes jealous of the members of this group and others like them – those who it seemed life had only smiled upon. Tony didn’t realize that each member of this group was subject to the same wants, desires, fears, and anxieties that Tony himself was subject to. He had yet to realize that they too, simply by virtue of being human, would experience suffering and pain, each in their own way. He had yet to see them as fellow sentient beings, brothers and sisters on the journey of existence. But they were. And Tony would understand that with time.”

With Tony, I’m hoping that, in time, I can naturally see others as my brothers and sisters.

Thomas Merton | Meditation to Contemplation in the Catholic Tradition

“Direct exposure to supernatural light darkens the mind and heart, and it is precisely in this way that, being led into the ‘dark night of faith,’ one passes from meditation, in the sense of active ‘mental prayer,’ to contemplation, or a deeper and simpler intuitive form of receptivity, in which, if one can be said to ‘meditate’ at all, one does so only by receiving the light with passive and loving attention…

The purpose of monastic prayer: psalmodic, oratio, meditation, in the sense of prayer of the heart, and even lectio, is to prepare the way so that God’s action may develop this ‘faculty for the supernatural,’ this capacity for inner illumination by faith and by the light of wisdom, in the loving contemplation of God. Since the real purpose of meditation must be seen in this light, we can understand that a type of meditation which seeks only to develop one’s reasoning, strengthen one’s imagination and tone up the inner climate of devotional feeling has little real value in this context. It is true that one may profit by learning such methods of meditation, but one must also know when to leave them and go beyond to a simpler, more primitive, more ‘obscure’ and more receptive form of prayer.”

Thomas Merton | Always Beginners

“The work of the spiritual father consists not so much in teaching us a secret and infallible method for attaining to esoteric experiences, but in showing us how to recognize God’s grace and his will, how to be humble and patient, how to develop insight into our own difficulties, and how to remove the main obstacles keeping us from becoming men of prayer.

Those obstacles may have very deep roots in our character, and in fact we may eventually learn that a whole lifetime will barely be sufficient for their removal. For example, many people who have a few natural gifts and a little ingenuity tend to imagine that they can quite easily learn, by their own cleverness, to master the methods – one might say the ‘tricks’ – of the spiritual life. The only trouble is that in the spiritual life there are no tricks and no short cuts. Those who imagine that they can discover special gimmicks and put them to work for themselves usually ignore God’s will and his grace. They are self-confident and self-complacent. They make up their minds that they are going to attain this or that, and try to write their own ticket in the life of contemplation. They may even appear to succeed to some extent. But certain systems of spirituality – notably Zen Buddhism – place great stress on severe, no-nonsense style of direction that makes short work of this kind of confidence. One cannot begin to face the real difficulties of the life of prayer and meditation unless one is first perfectly content to be a beginner and really experience himself as one who knows little or nothing, and has a desperate need to learn the bare rudiments. Those who think they ‘know’ from the beginning will never, in fact, come to know anything.

People who try to pray and meditate above their proper level, who are too eager to reach what they believe to be ‘a high degree of prayer,’ get away from the truth and from reality. In observing themselves and trying to convince themselves of their advance they become imprisoned in themselves. Then when they realize that grace has left them they are caught in their own emptiness and futility and remain helpless. Acadia follows the enthusiasm of pride and spiritual vanity. A long course in humility and compunction is the remedy!

We do not want to be beginners. But let us be convinced of the fact that we will never be anything else but beginners all our life!”

Thomas Merton | Darkness and Light

“This alteration of darkness and light can constitute a kind of dialogue between the Christian and God, a dialectic that brings us deeper and deeper into the conviction that God is our all. By such alternations we grow in detachment and in hope. We should realize the great good that is to be gained only by this fidelity to meditation.”

Thomas Merton | Flowering in the Desert

“The climate in which monastic prayer flowers is that of the desert, where the comfort of man is absent, where the secure routines of man’s city offer no support…”

Thomas Merton | Face to Face with the Sham

“After all, some of the basic themes of the existentialism of Heidegger, laying stress as they do on the ineluctable fact of death, on man’s need for authenticity, and on a kind of spiritual liberation, can remind us that the climate in which monastic prayer flourished is not altogether absent from our modern world. Quite the contrary: this is an age that, by its very nature as a time of crisis, of revolution, of struggle, calls for the special searching and questioning which are the work of the monk in his meditation and prayer. For the monk searches not only his own heart: he plunges deep into the heart of that world of which he remains a part although he seems to have ‘left’ it. In reality the monk abandons the world only in order to listen more intently to the deepest and most neglected voices that proceed from its inner depth.

This is why the term ‘contemplation’ is both insufficient and ambiguous when it is applied to the highest forms of Christian prayer. Nothing is more foreign to authentic monastic and ‘contemplative’ (e.g. Carmelite) tradition in the Church than a kind of Gnosticism which would elevate the contemplative above the ordinary struggles and sufferings of human existence, and elevate him to a privileged state among the spiritually pure, as if he were almost an angel, untouched by matter and passion, and no longer familiar with the economy of sacraments, charity and the Cross. The way of monastic prayer is not a subtle escape from the Christian economy of incarnation and redemption. It is a special way of following Christ, of sharing in his passion and resurrection and in his redemption of the world. For that very reason the dimensions of prayer in solitude are those of man’s ordinary anguish, his self-searching, his moments of nausea at his own vanity, falsity and capacity for betrayal. Far from establishing one in unassailable narcissistic security, the way of prayer brings us face to face with the sham and indignity of the false self that seeks to live for itself alone and to enjoy the ‘consolation of prayer’ for its own sake. This ‘self’ is pure illusion, and ultimately he who lives for and by such an illusion must end either in disgust or madness.

On the other hand, we must admit that social life, so-called ‘worldly life,’ in its own way promotes this illusory and narcissistic existence to the very limit. The curious state of alienation and confusion of man in modern society is perhaps more ‘bearable’ because it is lived in common, with a multitude of distractions and escapes – and also with opportunities for fruitful action and genuine Christian self-forgetfulness. But underlying all life is the ground of doubt and self-questioning which sooner or later must bring us face to face with the ultimate meaning of our life. This self-questioning can never be without a certain existential ‘dread’ – a sense of insecurity, of ‘lostness,’ of exile, of sin. A sense that one has somehow been untrue not so much to abstract moral or social norms but to one’s own inmost truth.”